There Is No Snapping Back

Two powerful films depict how the trauma inflicted by brutal regimes lasts for decades.

After a year of denial, I’m finally terrified. The unfolding events in Minneapolis, my beloved hometown, are a turning point. My naive hope that society will snap back to something approaching normalcy, or at least respect for civility and the rule of law, is increasingly feeling like self-delusion. Instead, I’ve been thinking a lot about collective trauma. Collective trauma is an event that rips the fabric of society. Ripped fabric is hard to repair and leaves a lasting mark.

Two movies, The Secret Agent and It Was Just an Accident, have resonated greatly with me as our country is fast slipping into an authoritarian, lawless state. Both deal with the collective, persistent impact of living in a state that inflicts terror on its citizenry. What struck me most is how long it took the societies to recover. Both films, which I highly recommend, explore how trauma persists, how things don’t snap back to normal, how the scars do not go away, even 50 years later.

The Secret Agent is set in Brazil in the 1970s, when a brutal military junta ruled the country for more than 20 years. While ICE is not executing students and other dissidents, there are a troubling number of similarities between our current state and Brazil. While things are not yet this bad, it is instructive to look at the instruments of power the military used to suppress dissent and consolidate their power.

Brazil’s military dictatorship (1964–1985) is often called the “Years of Lead” (anos de chumbo) because of the pervasive political violence, repression, and atmosphere of fear that characterized its most brutal phase, especially after 1968. The phrase evokes both bullets (“lead”)—symbolizing torture, disappearances, extrajudicial killings, and armed repression—and weight, capturing the suffocating pressure placed on civil society once the regime suspended constitutional guarantees under Institutional Act No. 5 (AI-5). During these years, censorship was total, opposition was criminalized, and the law functioned as an instrument of force rather than protection, leaving a legacy of trauma that persisted long after Brazil’s formal return to democracy.

The regime’s effectiveness was the use of Institutional Acts (AIs). These were supra-constitutional decrees that superseded the Constitution itself. Sound familiar?

Again, things here are clearly not as bad as Brazil in the 70s, not that bad, but many of the legal mechanisms resonate and lay out a path not dissimilar to the administration’s direction.

Directed by Kleber Mendonça Filho and set during the stifling atmosphere of Brazil’s military dictatorship in 1977, The Secret Agent (O Agente Secreto) is a political thriller starring Wagner Moura as Marcelo, an academic technology expert attempting to run from the regime by fleeing to Recife, only to find the city suffocated by state paranoia and surveillance.

The Secret Agent moves in time from the 70s to the preset day, where a history student, tracks down the Macrelo’s adult son to reveal evidence proving his father was not a criminal, but a dissident assassinated and framed by the state. This interaction illustrates the persistence of trauma, in which the student researcher bears the heavy psychological burden of resurrecting a truth the regime successfully erased, forcing the modern generation to finally confront the cold, unhealed wounds of their parents’ history.

The film is a critical darling. At the Cannes Film Festival, it won both best director and best actor (Wagner Moura). In the U.S., the film won the Golden Globe for best international film and a second best actor win for Moura. This week, it was nominated for the best picture and best actor Oscar.

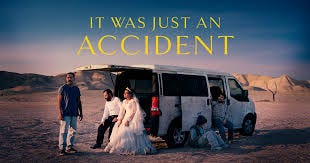

The second film, It Was Just an Accident, is set in a very different time and place but addresses similar issues. Released in 2025 and winner of the Palme d’Or at Cannes, It Was Just an Accident (Un Simple Accident) is a searing thriller by the Iranian director Jafar Panahi. The film follows Vahid, a mechanic and former political prisoner, who identifies a customer—a mild-mannered man named Eghbal—as his former torturer solely by the distinct squeak of his prosthetic leg. The title is derived from the film’s opening scene: Eghbal accidentally runs over a stray dog, and as his daughter weeps, his wife comforts her by repeating, “It was just an accident.” This phrase becomes the film’s central, bitter irony, symbolizing the banality of evil, in which perpetrators of state terror rationalize their systematic violence as mere occupational hazards or historical mistakes devoid of malice, while their victims remain trapped in their pain.

In our country, it is still too early for any cultural reaction to the cruelty of the current administration. We will have to wait for the films, novels, songs and art work that will help process the violent scarring of the country’s social fabric. Let’s pray we don’t get too much more raw material to work with.

Thanks for your Substack today! I think the last thing we want folks doing right now is to turn away from the accelerating oppression and its accompanying impunity. We live in a fascist state, and denial is not going to help us find a way out. So I think it helps to be mindful about the collective trauma that we are now experiencing - as an important piece in helping us care for ourselves and each other, and getting us to where we need to be before we are enveloped in a generation of trauma, such as is chronicled in those films (of which I have seen neither but will put them on my to-view list).

What’s happening in Iran right now is being starkly ignored by mainstream media and student protesters, yet it has everything to do with all of us, here and around the world about what it means to fight for human dignity, the worth and value of the lives of the most vulnerable, and the precariousness of the moral world. To see young girls standing up for freedom with no weapons other than their own human hearts is one of the most staggering examples of courage I’ve ever seen. We could all learn from them and I hope the world will step up for them as soon as possible.